> Strategies of Reclaiming

Michelle Teran

FADE IN

INT. OFFICE SPACE DAY

An office space somewhere in Madrid. IRENE, a psychologist, sits with MARILO, MANUELA, GLADYS, and CHARO. It is a hot, late afternoon in summer. IRENE sits to the far left of the room, the other four women sit in a semi-circle around her. All five women are wearing ‘Stop Evictions’ t-shirts. IRENE begins the session.

IRENE: I am going to tell you how we were thinking about working. What we are going to do is a discussion group. During the next hour, we are going to talk about our experiences of being affected by the mortgage crisis. We intend to document, first amongst ourselves, and then later with other people affected by the crisis, what the psychological impact of everything that has to do with eviction has been. This forms part of the work of the Truth Commission and also the Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH, an anti-eviction movement). This workshop is a test. The idea is also that afterwards, if you want to, you can become part of the team so that you are not just a participant, and then you can also help other people talk about their experiences within future group discussions. The first thing we want to do, because Marilo is suffocating from today’s heat, is to take a couple of minutes where we relax. Loosen your feet a bit. Your arms. Make sure you are comfortable in your seats, so that we can be a bit relaxed. Close our eyes and concentrate on a peaceful place, like a beach, where we are alone.

MARILO: We can’t stay there or I will fall asleep.

[Everybody closes their eyes except for Irene.]

IRENE: We are not going to stay there long, you will not fall asleep. Just until we are a bit relaxed. Try to feel the stress leave your arms. Move your shoulders a bit. Feel this tension and feel how it leaves the body. Think about a place that relaxes you. Like a beach with the breeze blowing. Pay attention to your breath. The stress is going away from your arms, your hands. Okay, we’ll slowly open up our eyes. A little calmer now.

[Marilo, Gladys, Manuela, and Charo open their eyes again.]

IRENE (cont’d): Okay, the theme that we wanted to propose to you today is that we talk about how we were before.

[Marilo, Gladys, Manuela, and Charo look at Irene.]

IRENE (cont’d): How was your life before you knew you were going to be evicted? Before you stopped paying for your mortgage? How did you feel? What ideas did you have for the future? To open up the discussion, in order to talk about this, the first question would be to say two or three adjectives, characteristics, of what others saw in you. For example, me, Irene, I would say that two years ago my best friends saw me as a girl, student, and a good friend.

[Irene looks at Marilo.]

This essay begins in a sweltering hot room during a Madrid summer. A small group gathers together to share stories of their emotional brush with eviction. The intimate conversation is part of pilot research on the psychosocial impacts of eviction carried out by a small team of researchers under the auspices of the PAH, an anti-eviction movement active throughout Spain. I position my role within the space and among the gathering as an embedded artist and researcher. I sit behind the camera, recording.

Throughout the text, I will describe several encounters with approaches instituted by the PAH, which they use to generate a set of audibilities that communicate the effects of an economic crisis and its societal impact on the personal lives of individuals. I will look at how strategies developed within grassroots, horizontal social movements like the PAH point towards situated, embodied forms of knowledge production; knowledge produced through practice. Several artistic works produced during my three-year artistic research project on crisis subjectivities will accompany the text. They are reflections, responses, translations, and remodeling of methodologies by the PAH and their strategies of reclaiming. By giving these examples, I want to consider the experimental practices developed by the movement as social pedagogy and based on principles of commoning, and how knowledge gained from these practices can broaden one’s knowledge and topics present in educational institutions.

The Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH), or the Mortgaged Victims Platform is a politically independent, non-violent, leaderless, right-to-housing movement. The PAH first appeared in Barcelona, February 2009, during the onset of the 2007/08 global financial crisis. Citizens, first with rising interest rates and later unemployment, faced an increase in financial difficulties and were unable to make their mortgage payments. In proportion to the dimension of the problem, the growing mortgage drama and the ensuing eviction crisis that was faced by thousands of families were barely discussed in the media; neither was it considered by the government. The PAH was set up to offer a network of solidarity and support, to fill in the gap in insufficient measures within government for dealing with the housing crisis, and to make visible the abuses of power by the financial system.1 At first marginal, and relatively unknown, the PAH came to fruition during the Spanish Occupy (15M) movement, when demands for more focus on real issues surfaced. After the initial public cry of outrage and the occupation of public squares in major cities throughout Spain, the 15M movement wanted to take the next step by solidifying its objectives. The PAH’s previous work, with their focus on housing, provided an ideal starting point for 15M. The PAH experienced significant growth (creating new PAHs connected to the assemblies of 15M), and the concentrations to stop evictions strengthened in number and force (Colau and Alemany).

A multidisciplinary team of students and professionals from various fields—social work, psychology, and political science—comprised the group for a pilot research project on the psychosocial effects of eviction. The team aimed to test out and build up a set of methodologies for future research, which could be implemented by other PAH groups and on a national level. Irene Montero, the principal researcher who proposed the pilot project, was an activist in PAH Madrid and engaged in other activities and campaigns.2 The four women participating in the pilot project were regular attendees of ‘Mutual Support and Empowerment’ workshops held twice monthly by Irene Montero, a PAH activist and psychologist. Montero initially put forth the proposal for the pilot project based on the practical knowledge gained from running the workshops. Eviction is an intense, emotional experience. The Mutual Support and Empowerment workshop provided a space for people to come and talk about their stress, depressions, and feelings of alienation. The four participants were also politically active in the PAH. After coming to the PAH with their housing problems, they became activists themselves and now dedicated much of their time and energy to helping others. In a series of group discussions, the researchers asked the participants to describe their experiences of how they are living with eviction. We met together for one hour, once a week, for one month. I made video and audio recordings of all four group discussions. The team used the recorded material for analysis and identification of emerging narratives and themes which they published in a report. I developed a film and script for public performance from the research.

While at first glance this might seem to be a relatively straightforward use of a qualitative method within a scientific research project, taken in a broader context one can recognize similar approaches present in other activities in the PAH. They encompass fundamental working methods used by the social movement. For the rest of the essay, I wish to give an overview of three essential elements:

Creating Audibilities—Microhistories

Let’s start with an example. Your name is Gladys. You have a job, a daughter, a house, and a mortgage. You work in a restaurant, sometimes six days a week. Your daughter says you work too hard, but you like to work and be busy, so this is okay. For many years you rented an apartment, at a high cost. Madrid is not a rental market, and the rental prices are excessive. Everybody around you, your friends, family, government, banks, newspapers, on the television as well, says that paying rent is throwing away money for nothing, and it is much better to own. The housing market is booming, and everybody should take advantage of this opportunity. Eventually you decide to follow what everybody else is doing and take on a mortgage. It’s a good investment; you can always sell and probably for much higher than the original purchase price. However, you are not interested in selling. You bought the apartment to make a home for you and your daughter. It is a good time for both of you. You feel emotionally and economically well and accepted by other people. One day you have a severe accident at work, which requires a series of operations. You go on sick leave. Because you are out of work for so long, you eventually lose your job. Even with the disability payments you have trouble keeping up with the monthly mortgage payments and make a difficult decision to stop paying for the house, and instead use what little money you have for other household expenses like food, utilities, and your daughter’s school costs. Spain is now in the throes of a financial crisis, and nobody is buying any property. Even if you wanted to, you wouldn’t be able to sell your home, and not at the original buying price. You don’t tell anybody, not even your daughter or your sister who also lives in Madrid. You attempt to negotiate a workable solution with your bank and they treat you like a piece of dirt, leaving you humiliated and weak. Instead of a client, you feel like an unwanted guest. You experience an overwhelming feeling of shame. You have failed everybody, including yourself. For days you don’t get dressed or put on makeup, and you stop dyeing your hair. You spend days in the house, feeling anxious. Some days you eat everything in the fridge because of the anxiety. Other days you eat nothing and stay in bed all day, watching television, but not watching it at the same time. The bank starts to contact you by telephone, by mail. Each time you open up the mailbox, it is an emotional blow.

One day there is a knock on the door. Two people say that they are from the court. One carries a machine, the other a notice of judicial foreclosure. They tell you to get a lawyer, or whatever, because you are going to be evicted. You sign the form, then go back into the living room, full of negative feelings about your life. Your partner, instead of offering you support, blames you for your situation. He tells you that because you took on the debt, it is your responsibility to pay it back. Instead of acting like a lover, he acts like a banker. You feel completely overwhelmed and disempowered. Even if you leave the property, you will still be left with the mortgage debt and with such a bad credit rating that it will be impossible to return to a state of normalcy. You have tried to follow a line, a dream, a future. But now you feel like you have fallen into a hole from which you cannot escape.

GLADYS: Listen, I gave all of my life to be there. I worked so hard, more than twenty-four hours a day, to be able to make the payments. And so you think, ‘Where am I going to end up? Where am I going to go?’ There are periods during the whole process where you might build up a bit of strength and think that you no longer place any value in material things. It’s true, but it’s a mixture of things, because you are also within your experiences.

The story of Gladys is a retelling of one of the stories shared during the pilot research project. It follows the primary tool employed by the movement of using personal narratives to investigate the structural causes, from which individual problems arise. The PAH operates on a model of collective guidance and collective learning. Storytelling, to a group of strangers, who later become friends and comrades, is the first step to putting a voice to an insurmountable issue.

People curious about joining the PAH can have their first introduction by attending a weekly public assembly. Anyone attending the meeting can add their name to a list and use the space to voice their questions and difficulties. The room quickly fills with stories. During the two-hour gathering, somebody offers an account of a particularly humiliating experience with a bank official, who refused to give them an important document that they had requested. Another talks about her uncertainty of how to negotiate with the bank, to modify the conditions of the mortgage. Somebody is experiencing an onslaught of aggressive techniques by the collection agency—telephone calls, emails, and visits to their place of work—for reclaiming the debt. Another just received the first notice of foreclosure in the mail and is at wit’s end. After sharing a personal story with a group, a question is put forth: ‘Has anybody else in the room had a similar experience? Can anybody advise this person?’ Most often, there are several people with the same story, or something comparable, who can provide some preliminary guidance, orientation, and support for the newcomer. Ada Colau and Adriá Alemany, two of the founders of the PAH, describe what unfolds during these meetings as such:

In this situation, many families come to the PAH with an absolute need to speak and to be heard. Thus, after overcoming an initial shyness, they seek ways of expressing the avalanche of emotions that have shaken them. Therefore, the first objective of the PAH is to create a space of trust and community through meetings, which give them the opportunity to express themselves and share their experiences with others. Building this space and linking personal experiences is vital in order for those affected to realise the collective dimension of the problem and that there are structural elements that have influenced our decisions. This process of absolving oneself of blame is a necessary step towards empowerment (Colau and Alemany 90).

What follows are the next stages of the process and steps for action. Newcomers can join bank groups who form separate workgroups where, for example, people with mortgages at the same bank can put forth their demands in a collective manner, and organize group actions. They can range from submitting en masse negotiation demands of pending cases to a bank manager, or showing solidarity by accompanying an individual to her appointment with the bank. Someone in the room might be about to be thrown out of their apartment during the week, which requires stronger forms of direct action. In the most acute cases, there might be a need to organize an eviction blockade. The PAH organizes these; people assemble in front of the building, to prevent the police and the bank commissioner from entering the apartment and finalizing the procedure. Finally, a formation of another group might be required, based on new problems and questions that emerge during the weekly meetings. For example, in the last few years, the sales of public housing units to American-based vulture funds generated new cases of evictions from housing designed to assist low-income families. The welcome assembly, in multiple forms and functions, acts as a forum for collective guidance, and mutual learning. It transforms an individual problem into a social issue.

This approach uses individual stories to create a context where social issues are made audible, and in this way underpins the systemic links to personal trauma.3 An empathic, active practice of listening to storytellers telling their stories forms the fabric of the collective struggle. Storytelling occurs in public assemblies, in workshops, during street demos, inside private apartments during evictions, and discussion groups. I want to propose the term ‘microhistory’ as a potential tool for thinking through this practice of giving personal upheaval a public voice. Microhistory refers to a particular approach to historical research, which uses a personal biography of an everyday person to build up a portrayal of the social, economic, and political environment of the individual’s reality. In microhistorical research, the agency of the individual opens up a historical process rife with conflicts and negotiations, with the possibility of several outcomes which are symptomatic of that particular time-space continuum. The microhistorical approach centers on scalability: zooming in to study the fragments, then scaling out to see everything at once, you become confronted with a ‘cross-cut’ of the world. Larger complex systems are investigated through the lens of individual stories and struggles, based on the evidence of personal accounts and testimony.

‘Microhistory’ was first coined by a group of Italian historians at the University of Bologna in the ’80s. The group experimented with approaches coming from literature to perform historical research in another scale; from the micro, the detail, the close-up, the overlooked. Literature offers many examples of history told from below and told by ‘non-famous’ people who are just trying to get on with their lives, their struggles, successes, and failures. The Italian microhistorians saw the possibilities of the literary method. Their primary influences traced back to the work of the French Oulipo school of experimental literature and work of George Perec, Raymond Queneau, and Italo Calvino, the latter who introduced the works of the experimental writers to the Italian historians.4 French writer Georges Perec, for example, is best known for his attention to detail and the spatiality of his writing. His novel Life: A User’s Manual takes place in a fictional apartment building on a fictional street in Paris, 11 Rue Simon-Crubellie. Each chapter focuses on a different apartment in the building, where the reader encounters various residents both past and present. There is movement between different temporalities and spaces, the attention placed on domestic artifacts—pictures, paintings, objects, furniture – together which give shape and distinctive character to the individual (Perec). It is perhaps not by chance that Carlo Ginzburg—one of the better-known microhistorians—recognized the promise of the new historical approach. The historian’s mother, Natalia Ginzburg, was a renowned author whose works centered on family relationships during the Italian dictatorship (Ginzburg, N). Ginzburg’s most famous work, The Cheese and the Worms, narrates the life of Domenico Scandella, also known as Menocchio, a miller living in sixteenth-century Italy, on trial for heresy. Ginzburg used transcripts from Menocchio’s court case, to bring to the forefront the so-called norms of the socio-cultural, and historical context addressed vis-à-vis Menocchio’s articulations, a figure of speech, references, and digressions during the trail (Ginsburg, C).

MARILO: This structural violence. It totally alienates each human story. Behind every family is a human story, one that is complex. When they take away a house, it is because of the economic value tied to it. But the consequences from these actions are not just economic ones.

Microhistory and the micro-historical method finds an allyship within a feminist practice which strongly resists the urge to control the narrative from the top down. Like microhistory, a feminist practice is a study of the macro from the micro, history from below. A chronicle of the here and now begins with valuing the knowledge that comes from personal experiences. Everybody has a story to tell, yet each story is unique. A story of a home might contain similar elements, yet is still different from other homes and the people who inhabit them; for whom trauma manifolds in diverse ways. Conscious raising, a primary organizing tool developed by second-wave feminists, is a method for giving a public voice to lived, painful experiences, exposing vulnerabilities. Individuals talk about their own experiences within small groups. Sitting around a circle, each takes a turn to give testimony to bring as many backgrounds and perspectives into a shared pool of knowledge. An underlying supposition to the practice is to use collective storytelling to build up an awareness of the systemic conditions underlying what that person might be living. Cooperative knowledge building is attuned to the relation and social content of what the group shares. Listening is the first step to building up knowledge, analyzing the social content and relationships to develop together with the next steps for further actions. A space for collective learning is therefore essential for creating audibilities, valuing other voices and experiences; using the lived experience and practice within the collective as a method for developing theory (Sarachild).

In her book ‘Living a Feminist Life’, Sara Ahmed relates a transformative experience in the early stages of her PhD studies when she comes across the works of black feminist writers Bell Hooks, Audre Lorde, and Gloria Anzaldúa. Within their texts, she encounters a form of writing theory where the ‘embodied experience of power provides the basis of knowledge.’ It is beyond the scope of this short essay to describe the work of these influential authors. What I want to highlight instead is how, according to Ahmed, these texts institute forms of theory that stem from lived experience and practice. The ideas formed in their literature emerge from lived experience, revisiting glimpses, moments, encounters, and dredging small details from the recesses of personal memory, for a more in-depth, more extended look of what had transpired and how that influenced feelings of self and position in the world. Their work has had a pivotal and lifelong influence on Ahmed’s theoretical work, in particular the refusal to practice the kind of theory that stayed within the safe confines of the abstract, and an interest in that which is situated within grounded lived moments of the everyday. As Ahmed claims, ‘the personal is theoretical.’ I want to end this section with Ahmed’s ‘idea of sweaty concepts’, which proposes a working methodology for practicing theory. On the one hand, concepts don’t emerge through detached, contemplative periods of reflection, but as a consequence of unfolding events. Conceptual work and descriptive work are, therefore, part of the same process. By working through something, you develop an understanding of how it works. Secondly, sweaty relates to a sweating body, a body under exertion, under stress. A body in distress is a body that is ‘not at home in the world’. The theoretical work strives for a conceptual understanding of this difficulty. ‘Sweaty concepts’ emerge from the ‘practical experience of coming up against the world or the practical experience of trying to transform the world’ (Ahmed 11–14).

The stories emerging from the PAH are vocal utterances of topics that would typically be considered ‘petty’: topics concentrating on the domestic space which suddenly become the focus of meetings and discussions. From a feminist perspective, the home has always been a political and highly contested space. It is also a space of violence. Starting with the knowledge that comes from experience, the lived experience of no longer feeling at ‘home’, one develops a broader understanding of the intersectional experience of racial, gender, and class oppression manifested in the public assemblies and beyond (Colau and Alemany 93). The lived experience of bodies ‘under stress’ helps develop both the theory and a set of practices within the movement.

GLADYS: Because two years ago, it was unthinkable to have been able to achieve everything that we have been able to achieve. This is the satisfaction I have for myself... that I have not just been able to overcome my own situation, but to help other people overcome theirs as well.

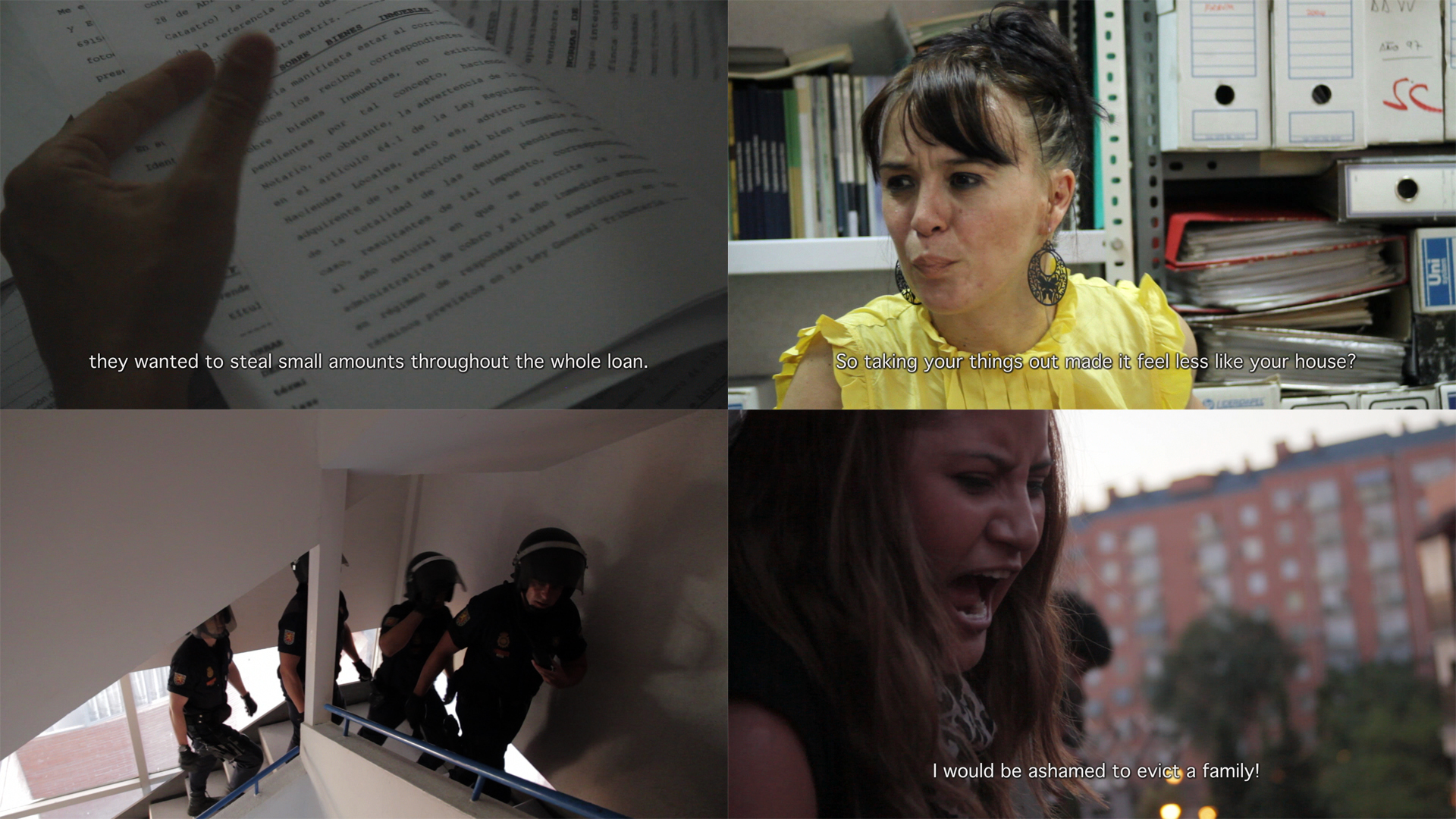

Mortgaged Lives, 2014, film, 42 min

Mortgaged Lives examines the experience of rupture through the loss of a home. The film analyses the psychosocial experience of eviction from three perspectives: psychological analysis, personal testimony, and an actual event.

Within the era of a global financial crisis, destabilization and displaceability define everyday reality, markedly felt around the home. Mortgaged Lives maps out the psychosocial trauma of homelessness, social estrangement, and the fight against injustice by those who are suffering the consequences of the economic crisis within the global economy. It documents the everyday realities of a contemporary crisis on individual lives. It shows the growing need and inspiring strategies for fighting injustice produced by a neo-liberal economy.

Open-source, distributable actions

The PAH operates as a decentralized network of groups and centers distributed throughout the country. Each group has the autonomy to develop campaigns and strategies appropriate to the local context. Campaigns and creative strategies function as open-source toolkits, free to be taken up and implemented in other spaces and locales, which are themselves open to further innovation and adaptation. In the previous section, I related some working processes for meetings, workshops, and discussion groups. Other strategic campaigns use more visible, creative, public actions to highlight concepts emerging from unfolding events. In the next section, I will discuss an example of one such campaign.

The PAH Obra Social is a campaign which reclaims empty residential properties owned by banks and offers them to evicted individuals and families who have been made homeless. Housing activists target buildings constructed during the height of the housing bubble (from 1996–2008), yet which were left vacant and unoccupied. Banks are the current owners of these buildings; they took over possession of the property from bankrupt developers who defaulted on their investment loans. While people went through painful evictions from their homes at unprecedented levels, banks held not only huge parcels of residential properties but were recipients of massive bailouts by the government, using tax payer’s money. The PAH used these two tendencies to argue for the legitimacy of their actions: Since the public bailed out the banks, then empty homes in the hands of the banks belonged to the public.5

During an action by the PAH Obra Social, people publicly and defiantly enter empty buildings in their local neighborhoods. Once inside, amid much fanfare, people unfurl colorful banners out of the windows, hanging them down the front facade of the building. The long, vertical banners have hand-painted Obra Social logos, and slogans such as ‘We rescue people, not banks’, or ‘No people without houses, no houses without people’. A delegated person reads out a declaration of intent, issuing a public statement for the action in front of the building. This boisterous action is the culmination of a long preparatory period and an in-depth study of the area. Typically, the housing activists look for new buildings that are the property of financial entities and are currently vacant, giving priority to residential buildings owned by banks who received government bailouts. The group uses various techniques and preparatory procedures to locate a suitable vacant property. One of the best places to find potential candidates for buildings are on bank real-estate websites. To make sure that nobody is currently living in the building, on-site surveys, walking by the building at different times of day, checking for lights in the windows, piled up mail, or people entering and exiting the building, will give clues of any sign of ‘life’ (PAH).

The residential property, once occupied, becomes a building of the Obra Social, and part of a socially-engaged and political project. People living in the building must also contribute to the collective project by giving their time and energy towards maintaining the building. They must also commit time to help others in need with their local cities and neighborhoods. The performative action of entering, reclaiming, and renaming by citizens and activists returns a vacant, lifeless building to a public commons. Through such a gesture, it proclaims a different model for living, how one might take up space in the city. A radical claim for convivial ways of living, being and acting together spills out and spreads beyond its original point of action. It joins a network of Obra Social buildings, in Catalonia, Castilla-La Mancha, Asturias, Andalucia, Extremadura, Zaragoza, Valencia, and the Community of Madrid.6

The term ‘overspill’ or ‘desborde’ in Spanish, is both a working expression and fundamental modus operandi for Spanish post-occupy movements like the PAH, but undoubtedly notable in other social movements within and outside of Spain. Avoiding fixed ways of doing, creating and acting, ‘desborde’ is about plurality, and embracing a multitude of variations and adaptations to the original spark. It refers to a collective putting forth of a creative process that is difficult to control, yet predicated on a mutual desire to act.7 British cultural theorist Tony D. Sampson argues for how desire can act as a propagating agent for generating unplanned, fortuitous innovations. According to Sampson, desire takes on two distinct modalities. There are everyday desires based on basic human physical needs: to find shelter, food, clothing, a sexual companion. These basic desires are predictable and repetitive. Sometimes a desire, which starts from an everyday need, can take another turn and go down unexplored paths and take on a life of its own. These are ‘non-periodic desire-events’; forms of episodic and uncontrollable desire that have the potential to produce something wholly unanticipated and new. Innovations originating from basic needs arise in the way of ‘passionate interests, fashions, trends, and fads.’ What begins as a micro-event or action gets taken up, repeated, and propagated through networks, where repetitions of events and movements are themselves open to adaptation. It is performativity in action. Small innovations can have potentially wide-spread, transformative effects of ‘influence and overspill’, manifesting as the intended or unintended impacts of putting ideas into action (Sampson 114).

Losing control of the process and operating with the freedom to improvise using new tactics and methods means new forms and visibilities are created in other locales and contexts. Such forms are loosely coordinated yet autonomous actions, transmissions of social inclinations and ‘itches’ that are propagated from one body to another and who become transmitters and receivers of creative proclivities. Imagination and creativity are, in fact, one of the critical propagators of political action. The PAH, like many social movements, makes ample use of digital networks to launch and disseminate extensive campaigns that come out of fundamental and even humble needs, such as the right to housing. Images and image-making play a fundamental role in the political imagination, of putting thoughts and desires into action. For example, each recovery of a building by Obra Social generates new slogans, logos, maps, texts and graphics which the residents and activists use to circulate the methods, ideas, dreams, and desires of the campaign. Viral tactics drive the dissemination of symbolic (cognitive) capital through social networks, creating synergies of ideas which generate new ideas. They create intersections of different voices, and perspectives, bring non-official views to the foreground, build up forms of civic intelligence and civic subjectivities.

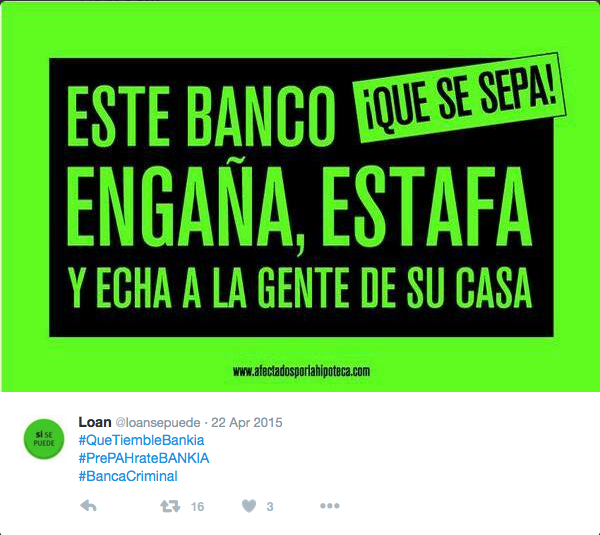

On April 22, 2015, at around 10.30 am, participants and organizers from The Obra Social accompanied approximately fifty other activists and ‘housing victims’, where they entered and occupied the central bank branch of Bankia in downtown Madrid for several hours. This move was part of state-wide action initiated by the PAH called PrePAHRate Bankia (loosely translated into ‘Prepare yourself Bankia’). Other branches in major cities throughout the country were synchronously entered and occupied. During the action, participants slapped down stickers with a graphic imitating the design scheme and colors of the bank’s official logo onto the cashpoints, walls, and windows of the branch. Using a détournement method, the PAH activists inserted a counter-message into the Bankia logo: ‘So you know! This bank cheats and steals, and throws people out on the street.’ The PAH’s reasons for focusing on Bankia were manifold.

Bankia received a bailout of billions of euros of (Spanish and European) public money, while at the same time having the dubious honor of executing the greatest number of evictions. The major bank was also under scrutiny for its revolving door policy wherein former bank executives took political positions, and vice versa. For example, Rodrigo Rato, former economic minister and head of the International Monetary Fund was acting president of Bankia until 2012, when it was declared bankrupt and in need of public bailouts. Around the time when the action was taking place he had just been arrested for ‘fraud, embezzlement, and money laundering’.8 Lastly, the activists focused on the ‘Social Housing Fund’ program created by Bankia three years prior, which was supposedly established to allocate social housing to people in need, but which had only served a symbolic function and never saw the light of day. The activists argued the crisis of affordable, social housing had been artificially created by the financial sector, and this became the main objective for the action. In Madrid, for example, there were thousands of unsold, unused properties in the hands of Bankia. Some people present during the bank action had illegally entered properties owned by Bankia and were currently undergoing prosecution for illegal entry by the bank. The activists’ demands were threefold; they demanded that the bank rescind the pending denouncements for unlawful entry, that it open up negotiations of social rent of 30% overall income for people already evicted so they could continue living in their homes, and lastly that the bank relinquish all unoccupied properties for social housing.9

During the action, people entered and completely took over the bank branch. They strung out clothing lines between the columns of the interior of the office, hung banners with the slogan ‘Bankia is ours and the homes too’. The protesters lay out picnic blankets, arranged food and drinks, and generally made themselves at home. Once established in the space, they proceeded to the next phase of the action. Two or three of the protesters milled around the room, gathering pending claims for social housing, collecting paperwork from those present in the room. Laden with a large stack of documents, the protesters demanded that the director of the bank accept the formal requests and demands presented by the group. During the day, the group made periodic announcements and formed assemblies to discuss the next steps of the action. Chants, manifesto readings, and speeches punctuated the occupation. Activists standing outside of the bank handed out information flyers to passersby and made statements to the media. Images of the live actions, which coincided in different cities and locations, were circulated on social media and moved between the sites of operation. The protesters, situated at bank branches in cities throughout the country, sent reports, keeping abreast of developments in their local regions.

An initial hijack of the Bankia logo created a chain reaction of memetic variations and creative interpretations which were also distributed and shared between the protests at local bank branches and those situated elsewhere monitoring the action. A meme of a snarling lion sent from León, a city in the northwest of Spain, stated ‘Prepare yourself Bankia, and the lion eats Bankias. The PAHs are angry.’ It was simultaneously a play on the city’s name, and the Spanish word for lion. Other PAHs offered proposals for ad-hoc actions to be taken up in different branches. For example, from Bilbao came calls to create disturbances by flooding the telephone lines at the central Bankia office. In the months that followed, the PAH activists used the hashtag #PrePAHrate in eviction blockade actions, bank negotiations and signing of social rent agreements, tying continuing activities to the campaign against Bankia.

GLADYS: I think that the most important thing throughout this entire process is that we make all of these cases completely visible. All of them... how they cheated us. We need to make sure that all the work that we do in this social movement is visible.

‘Rupture Sessions’, 2014, public reading

‘Rupture Sessions’ is a reenactment of a conversation between a psychologist and four women living in Madrid about their personal experiences with eviction.

Translated from original recordings in Spanish into other languages (English and French to date), the transcript is a testimony to the everyday realities of contemporary crisis, bringing personal experiences into universal issues around social rupture and the disintegration of the home. The public reading of the text is a discussion and analysis of the conversation through aesthetic reflection. Circulating and introducing translated text into other configurations and conversations give impetus for reflection on contemporary crisis and its impacts on the home, a cross-pollination of ideas which takes place within a dialogical situation.

Publication—Making things public

Throughout the essay, I have presented some typical cases of experimental practices used by the PAH. My observations partly come from being an active witness who has been embedded within some of the events chronicled in the essay. For example, to develop an understanding of the PAH Obra Social campaign I attended meetings of Obra Social Madrid and was present during several bank occupation actions and other demonstrations, and even accompanied some of the members to the annual state meeting of the PAH in Almeria. Additionally, I lived in one of the Obra Social buildings located in Mostoles (the outskirts of Madrid) for some time and attended regular plenary sessions by the local Stop Desahucios (Stop Evictions) and Obra Social groups.

In the previous account of the bank occupation, I introduced a technique of creating the conditions for the viral spread of information that moves across different platforms and channels of communications. Slogans, memes, mission statements, and photo-documentation of actions taking place within physical locations have other presences and currencies in other sites and to different audiences. The practice of hearing, recording, and creating audibilities for personal testimony transforms a traumatic event experienced by a single person or family into a profound social issue that impacts more people than the government and other institutions would like to admit publicly. The culmination of microhistories by ‘insignificant’ people creates a public face and account of a social crisis (Teran).

What I have attempted to show throughout the text is the importance of developing methods that create conditions for audibility, of ‘giving trouble a voice.’ All of these activities generate evidence, audibility, a trace. The act of publishing, of making things public takes on a vital element to movements emerging from urgent, situated, ‘practical experience of coming up against the world’ (Ahmed, 14). To register, to capture, to distribute, to circulate: these performative acts relate to an urgency to create a public record through the act of making things public; to reach and share with another audience who might not be immediately present. In these examples, the documentation does not materialize at the end of the work. It is practiced daily, in real-time, as an essential component to the project.

I want to return to the Obra Social campaign to offer one representative case of publishing in action. The Obra Social Manual, developed by the PAH, is a twenty-five page manual of civil disobedience on the tactics of recuperating houses, a direct action how-to. It offers a step-by-step guide for reinstating the social use of empty housing owned by banks. It provides political bases for the project, outlines legal tactics, criteria for access, organizational strategies, and plans for building up solidarity and alliances; psychogeographic methods strategies for visual signage and visibility techniques. Additional resources and supplementary knowledge from squatting manuals provide other references for technical knowledge on how to set up basic amenities, such as electricity and water (PAH). The manual appeared in the early phases of the campaign (2013) when it was more of a speculative exercise than an established, wide-spread practice. The publication offers a preemptive visioning of alternate, innovative models for community building.

Almost since its inception, The PAH has made use of image professionals interested in building influential connections between art and social action. The group Enmedio, a collective of designers, photographers, filmmakers, and artists, frequently collaborates with the PAH and helps devise some of their (more spectacular) visual and performative action campaigns. The impetus for working with the PAH is their belief in images and image-making, and the transformative power of storytelling for social justice and social action. One of the enduring activities by Enmedio is a series of TAF! (Photo Action) Workshops that explore documentary photography as a medium for political work, and its relation between art and activism. They apply their skills to develop creative amplification strategies, bringing personal testimony to the public domain. In an ongoing campaign ‘No Somos Números’ [we are not numbers] the PAH works with Enmedio to focus its lens on the bank of Caixa Catalunya. Within the TAF! Workshop, participants lend themselves as subjects for portraits for a postcard series.

On January 10, 2019, Enmedio and PAH implemented some of the images and postcards produced from the workshop for a public action staged in front of the door of the central office of Caixa Catalunya in Barcelona. Using the postcards produced from the workshop, the collective invited the crowd of hundreds of people gathered in front of the building to fill out personal messages dedicated to Caixa Catalunya. Some wrote accounts of their housing difficulties on the back of the postcards. Others offered simple, to-the-point statements: ‘Thieves’, ‘You are taking our lives’, ‘One day you will be judged.’ In under an hour, most of the postcards had been filled out. The group taped the postcards around the main door of the bank. Additionally, they attached a few large posters of people currently enduring housing problems with the bank in question on the wall next to the postcards. There were many journalists present: photos of the action appeared in the morning newspapers the following day.10

Publishing and making things public is a political act. Publishing is a tool for thinking, following and reflecting: creating audibilities. A public announcement issued in front of a soon-to-be occupied building, a manifesto, press release, how-to manual, slogan, meme, poem, song, chant, list of names, map, logo, personal testimonial or banner: together they act as tools for generating traces, public records of transformative practices put into action. They trace out a history of reclaiming efforts: to reclaim agency, to reclaim narrative, dignity and (for the housing movement) to reclaim homes that were lost. They amplify the troubles, create a paper trail, point the spotlight at the guilty, and document crimes against humanity. They bring in multiple authors and perspectives, use a range of methods, approaches, and narrations. There is a value of preserving, publishing, disseminating, and re-working knowledge, built up in common. Bringing in the ecology of making a ‘public record’ of actions and processes, the politics in documentation takes into consideration the production methods, economy, authorship, and to which ‘public’ or knowledge circuits it aims to reach.11

‘Reclaiming Workshop’, 2016, public intervention

The ‘Reclaiming Workshop’ is an exchange of models and strategies on the relations between places, materials, and performative actions produced in the context of reclaiming. During the workshop, participants publicly read selections of published and unpublished material generated from their political struggles. Participants joining the workshop represent grassroots initiatives and affinity groups connected by the fight for the right to the city. The workshop uses manuals, manifestos, open letters, pamphlets, and other materials brought by the participants to the workshop in a collective reading performance. The event proposes the public reading and exchange of these materials as a bridge for dialogue and collective knowledge, building up a public archive through the circulation of instructions and recipes for living.

The workshop was developed for the Neighbourhood Academy 2016 program, which focused on forms of collective learning. Located in the Prinzessinnengarten—an urban garden located in Kreuzberg—the Neighbourhood Academy is a self-organized, community, and future-oriented education facility. The protest banners used by each of the participating groups were hung around the facade of ‘Die Laube’ and launched the event, designating it a space for collective learning.

Conclusion

The practices instituted by the PAH are valuable methods for assembling publicly voiced narratives, bringing individuals together in a collective struggle. It is no small feat what the PAH have managed to achieve. What began as a small, marginal experiment in Barcelona turned into a widespread movement where housing became a mainstream issue that was spoken about on all levels of society. Their achievements influenced the formations of new political platforms, like the progressive municipalist forms of governance in major cities throughout the country. Ada Colau, one of the founders of the PAH, is currently running her second term as mayor of Barcelona. It also gave many people the strength to take back control of their lives and to cultivate a critical and ethical practice of care towards others.

What can educational institutions learn from flexible, situated, radical, and DIY learning structures emerging within the social realm? What are the developing forms of education and pedagogical strategies connected to civic urgencies, political struggles, and spaces of resistance?12

Social movements practice social pedagogy. It is a social practice of pedagogy in action. Social pedagogy is not merely the transference of information or preparation for a future role based on how well you perform, nor is it a form of educational training that gives promise of a bright future. It is an ongoing, active reflection, revision, and emergence of processes and trajectories that respond to the here and now (Trogal 239–52). It considers how processes develop, how they are manifested, archived, and distributed. Social pedagogy is a practice of immanent unfolding; collective, socially-engaged and open to dynamic shifts and adaptations with experience. It considers which bodies are representative in a space, and how does a space impact the bodies present. It is a situated, embodied form of knowledge production, building networks of alliances around socio-political aims and for projecting alternatives. Approaches to skill sharing and co-creating knowledge encompass an integral part of what is considered as social practice in the cultural realm. Together you learn what you need to learn, because it is important to learn what you need to learn at that moment.

This is not a trivial statement, nor does it imply forever staying in the present without any insight nor projections of future impact. What is does allow for is a learning process, attuned and attentive that stays deep within a complexity of the trouble by maintaining proximity to the problem. Practice, thoughts, ideas and desires in action generate methods for thinking through the troubles; research which occurs from the ground up. This process develops theory; produces new ecologies whose initial effects might be perceived but whose long-term impacts might not be immediately evident. Social pedagogy builds up on experiences, ideas and skills; it forms a collective learning process that arises from the urgency of the context and terrain. It has a different agency and immediacy to what is currently practiced within ‘traditional’ educational institutions, who, by their very institutional make-up are unable to react, act and adapt at a similar speed.

How can academic institutions maintain their relevance within a present-day climate that requires more urgent, immediate and informal forms of education and organizing? How can we, as researchers and educators, start to address both the needs for more responsive, ‘response-able’ (Haraway) and ‘attuned’ (Tronto) forms of learning, that evoke competencies of deep listening, (Bloom) sensing, observing, responding, collaborating and sharing?

Creating a learning environment based on a deep attitude of caring (for people and the world) requires new approaches. They will require forms of sociality based on notions of the commons, that enlist highly inefficient practices (at least to the capitalist) of radical formations of communal, non-commodified spaces and communities. They will engage a method of ‘deep hanging’; embodied, embedded long-term engagement with contexts and spaces outside of the classroom. Educational approaches that challenge and disrupt power relations, power inequalities, and systems of oppression will be required as a fundamental baseline to move forward. Participating and immersing oneself in the form of sociality—where enough space must be given to discuss, share, and negotiate—is essential. It will place value on forms of knowledge production that is multigenerational and across cultures; ethical, interdependent practices between people, land, and natural resources.

The organisational structures ingrained in non-institutional learning spaces and political practices—economy, decision making, space, forms of learning, etc. —could provide useful models and guidelines for future learning, for long-term ecological pedagogical practices to meet present and future challenges. Within the essay I have focused on the PAH, offering several examples of methods developed and emerging from their political work. Other examples, such as recent climate camps by climate justice protesters like Fridays for Future13 or Extinction Rebellion14, manifest forms of educational exchange combining both practical skills sharing and knowledge exchange to help broaden the influence and impact of developing political struggles. Together these, and many other, examples of non-institutional educational practices, can provide useful role models for how we might want to learn, to live, or live with and be in the world. Practices that take into account more sustainable and flourishing relations, forms of situated knowledge building, to develop ‘sweaty concepts’ that foster relationships and alliances that are collaborative, rather than competitive and alienating.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press, 2017.

Bloom, Brett, and Nuno Sacramento. Deep Mapping. Breakdown Break Down Press, 2017.

Colau, Ada, and Alemany, Adriá. ‘Mortgaged Lives’. Translated by Michelle Teran. Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2014.

‘Fridays for Future.’ Fridays for Future, https://fridaysforfuture.de/. Accessed 28.08.2019.

Ginzburg, Carlo. The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-century Miller. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

‘Home’. Extinction Rebellion, 2019, rebellion.earth/. Accessed 28.08.2019.

PAH. ‘The Obra Social Manual’. Translated by Michelle Teran. Original Spanish version by the PAH. Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2016

Perec, Georges. Life, a User’s Manual. Boston: D.R. Godine, 1987.

Sampson, Tony D. Virality: Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks. University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Trogal, Kim, ‘Feminist Pedagogies: Making Transversal and Mutual Connections Across Difference’. In: Feminist futures of spatial practice: materialisms, activisms, dialogues, pedagogies, projections. Art Architecture Design Research, Spurbuchverlag, 2017, pp. 239–52.

Tronto, Joan. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. Routledge, 2015.

List of Images

1. Tweet from the PrePAHrate campaign: “This bank cheats, scams and throws people out of your house.” “@loansepuede. “#QueTiembleBankia. (Bankia trembles) PrePAHrateBANKIA. (prepare yourselves Bankia) #BancaCriminal” (criminal banking). PrePAHRate Bankia action. Twitter, 22 April 2015. https://twitter.com/loansepuede

2. Tweet from the PrePAHrate campaign: “León eats Bankias. You are going to swell up!!!!” @PAHSantaPola. @MENU PARA HOY: León come Bankias. OS Vais a hinchar!!!! (León eats Bankias. You are going to swell up!!!!) #PrePAHrateBankia.” PrePAHRate Bankia action. Twitter, 22 April 2015. https://twitter.com/PAHSantaPola

3. Image from The Obra Social Manual. Collective Recuperations. Translated by Michelle Teran. Original Spanish version by the PAH. Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2016, pg. 10.

4. No Somos Números. ction by Enmedio. 11 January 2013. Photo by: Oriana Eliçabe, Fotomovimiento.org y Consuelo Bautista.

From 2013 until today, there have been more than 700,000 evictions in Spain due to non-payment of mortgages and, in recent years, this figure has been increased by rent evictions. See: PAH, ‘Reunión de la PAH y la La Coalición Europea’, June 6–10, 2019, https://afectadosporlahipoteca.com/category/propuestas-pah/internacional/.

↩︎Irene Montero is a psychologist and member of the Podemos party since 2014. Montero left the PAH and joined Podemos one year after the pilot research. Since February 2017, she has been the Spokesperson for the Parliamentary Group Unidos Podemos-En Comú Podem-Galicia en Común in Congress.

↩︎The PAH uses first names and specific cases of people affected not because they want to abuse their personal stories, but to investigate the structural causes through individual experiences. I am using the first names of people within the text and artistic research with the same intent.

↩︎Interview with Carlo Ginzburg recorded in his apartment between 24–25.10.2014, Bologna. The conversation took place between Carlo Ginzburg, Magnus Bärtås, Andrej Slávik, and Michelle Teran under the auspices of the artistic research project Microhistories. Funded by the Swedish Research Council.

↩︎There are still approximately 3.5 million empty residential properties throughout Spain. Juan Carlos Arias, ‘Marga Rivas, portavoz de la PAH: “hemos visto 4 o 5 desahucios diarios durante el mandato de Carmena”’, Disquierdaiario.es, July 2, 2019, https://www.izquierdadiario.es/Marga-Rivas-portavoz-de-la-PAH-hemos-visto-4-o-5-desahucios-diarios-durante-el-mandato-de-Manuela.

↩︎There have been more than 4,000 people rehoused since 2011, and more than fifty buildings recovered from the banks. See ‘Hoy presentamos nuestra nueva campaña contra la criminalización de la ocupación’, @ObraSocial_PAH, Twitter, 3 April 2009, 1.03 a.m., twitter.com/ObraSocial_PAH/.

↩︎Gutiérrez, Bernardo. ‘Diez Claves Sobre La Innovación De La #ManuelaManía.’ Yorokobu, 22 May 2015, www.yorokobu.es/diez-claves-manuelamania/.

↩︎BBC, ‘Ex-IMF chief Rodrigo Rato’s home and office searched in Spain’, April 16, 2015, www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-32335842.

↩︎‘Habrá Más Desahucios Sin Alternativa Habitacional Si Bankia No Cede Pisos.’ Plataforma De Afectados Por La Hipoteca (PAH), 11 February 2016, afectadosporlahipoteca.com/2016/02/11/habra-mas-desahucios-sin-alternativa-habitacional-si-bankia-no-cede-pisos-2/.

↩︎‘No Somos Números’, Enmedio, 11 January 2013, http://www.enmedio.info/postales-y-retratos-fotograficos-contra-los-desahucios-de-calatunya-caixa/.

↩︎This formulation was developed in collaboration and after long conversations with Clara Balaguer, coordinator Social Practices, Willem de Kooning Academy. It is one of the working principles to Social Practices and areas addressed in the minor Performative Action.

↩︎This question emerges from conversations around The Neighbourhood Academy, a project of self-organized participatory education outside of the academy structured around notions of deep time learning ninety-nine years. It is being developed together with Marc Herbst, Marco Clausen and Asa Sonjasdotter, and taking place in the Prinzessinnengarten, Berlin.

↩︎‘Fridays for Future.’ Fridays for Future, fridaysforfuture.de/.

↩︎‘Home.’ Extinction Rebellion, 2019, rebellion.earth/.

↩︎